The Book of Invisible Women – 10 Movement Collection

$60.00 – $130.00

The Book of Invisible Women is a collection of ten musically related movements for string quartet. The ten essays are to be played in any combination and in any order. There is no optimal number that should be performed together, nor any optimal sequence. Individual movements are also available for purchase.

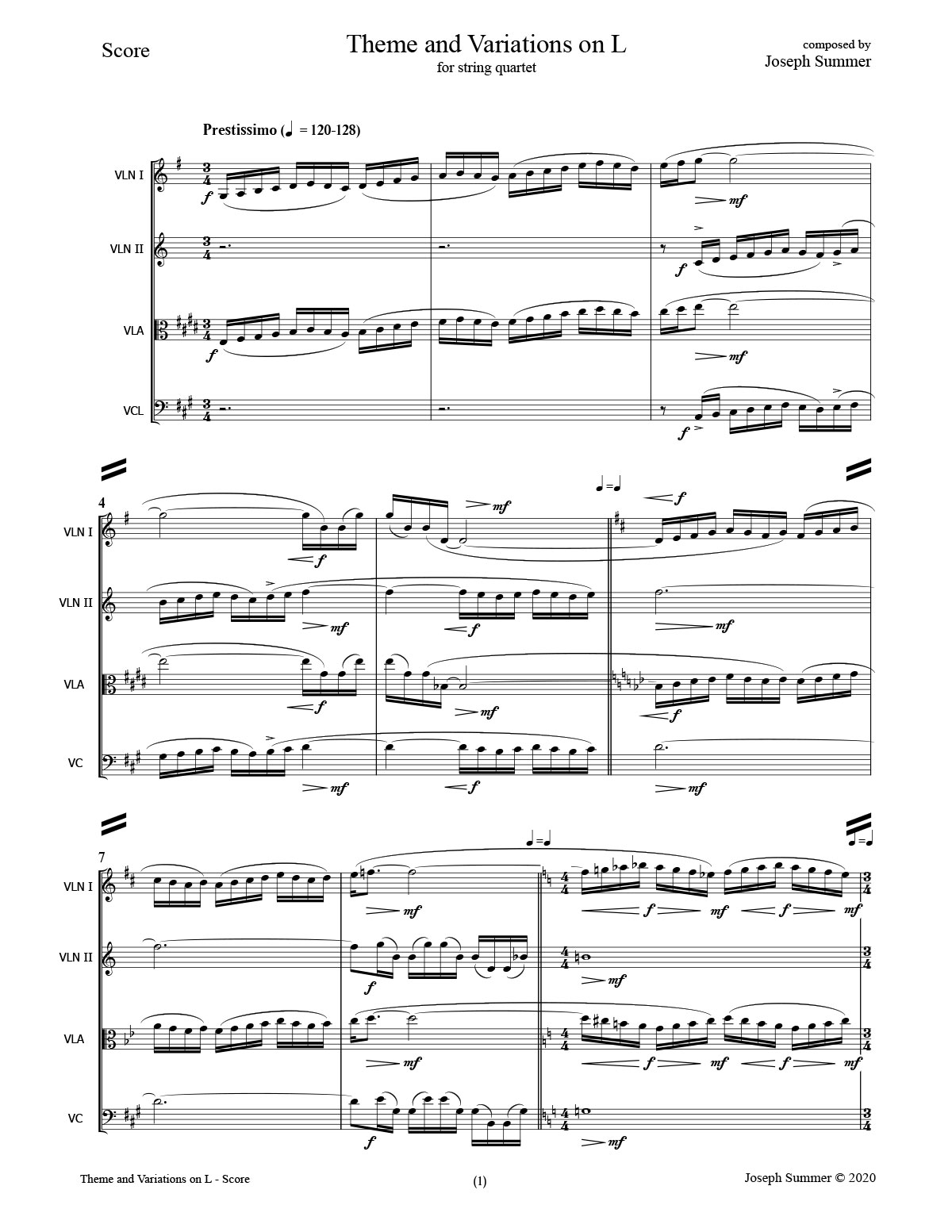

- Theme and Variations on L

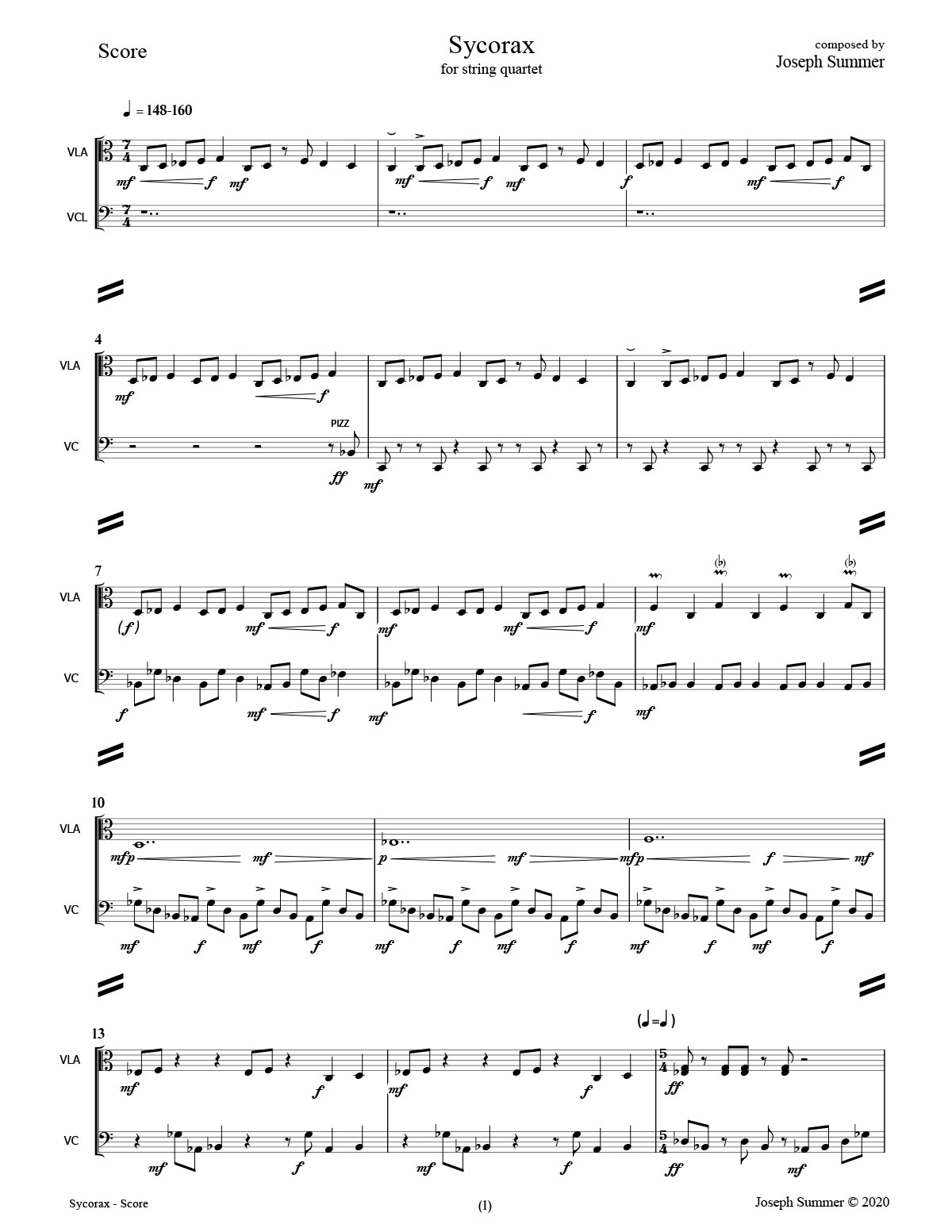

- Sycorax

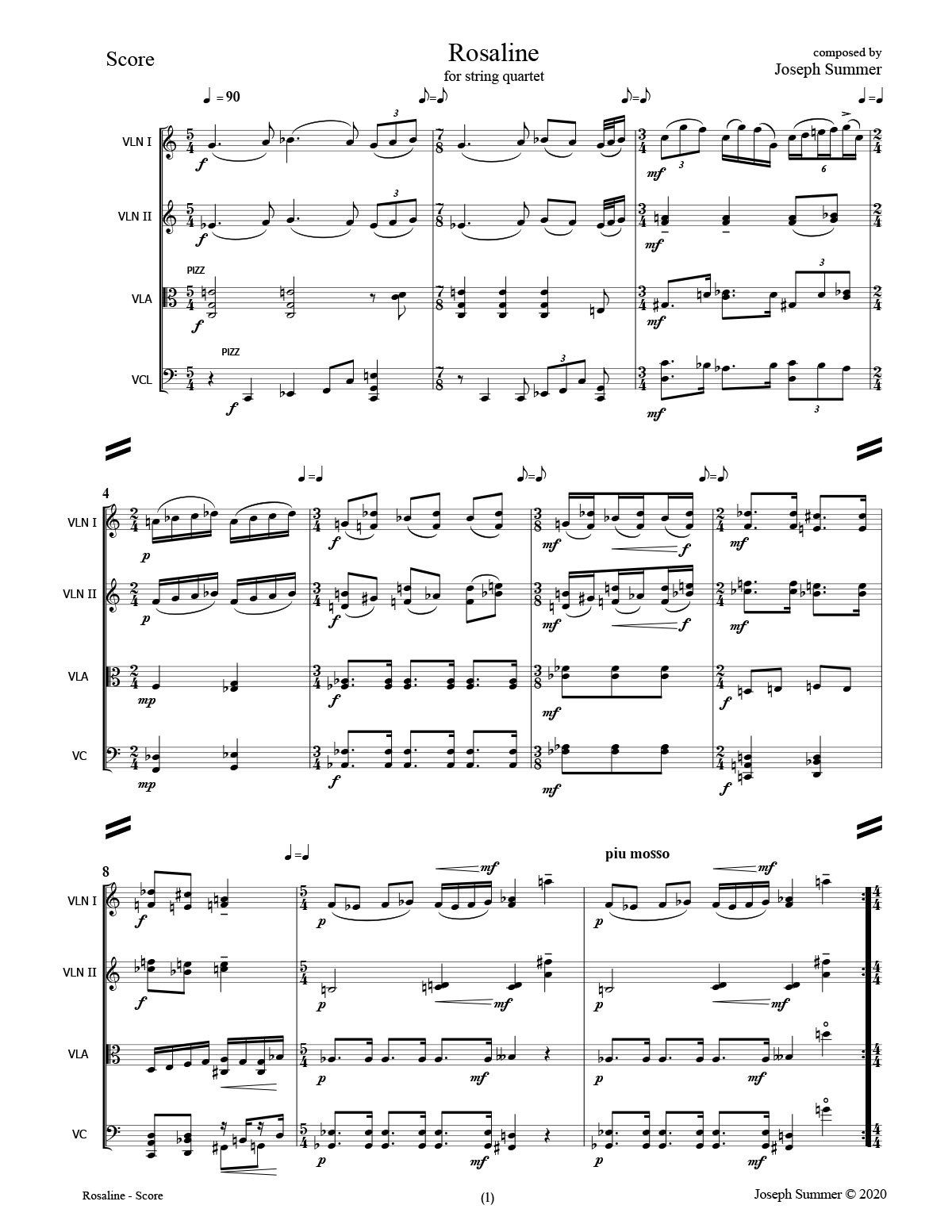

- Rosaline

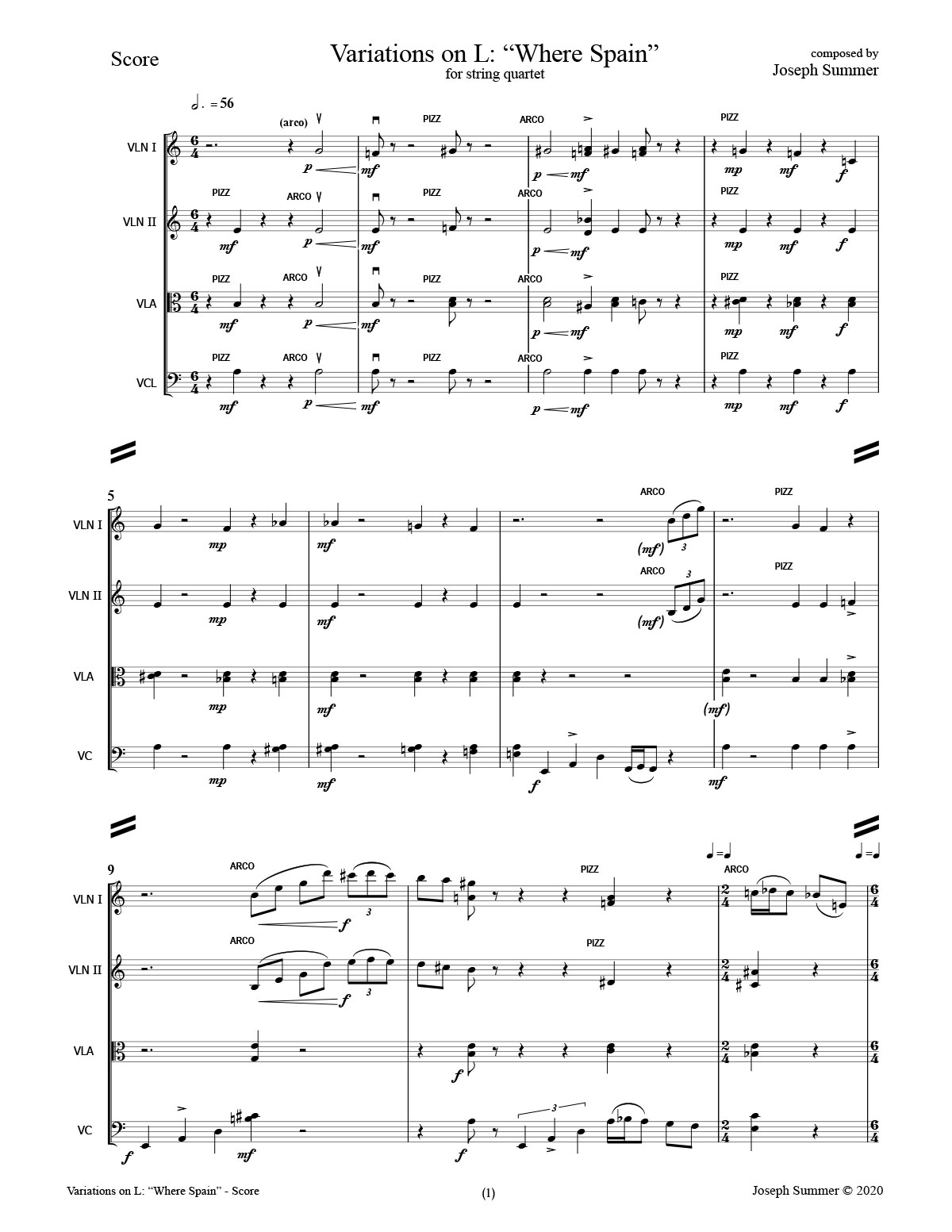

- Variations on L: “Where Spain”

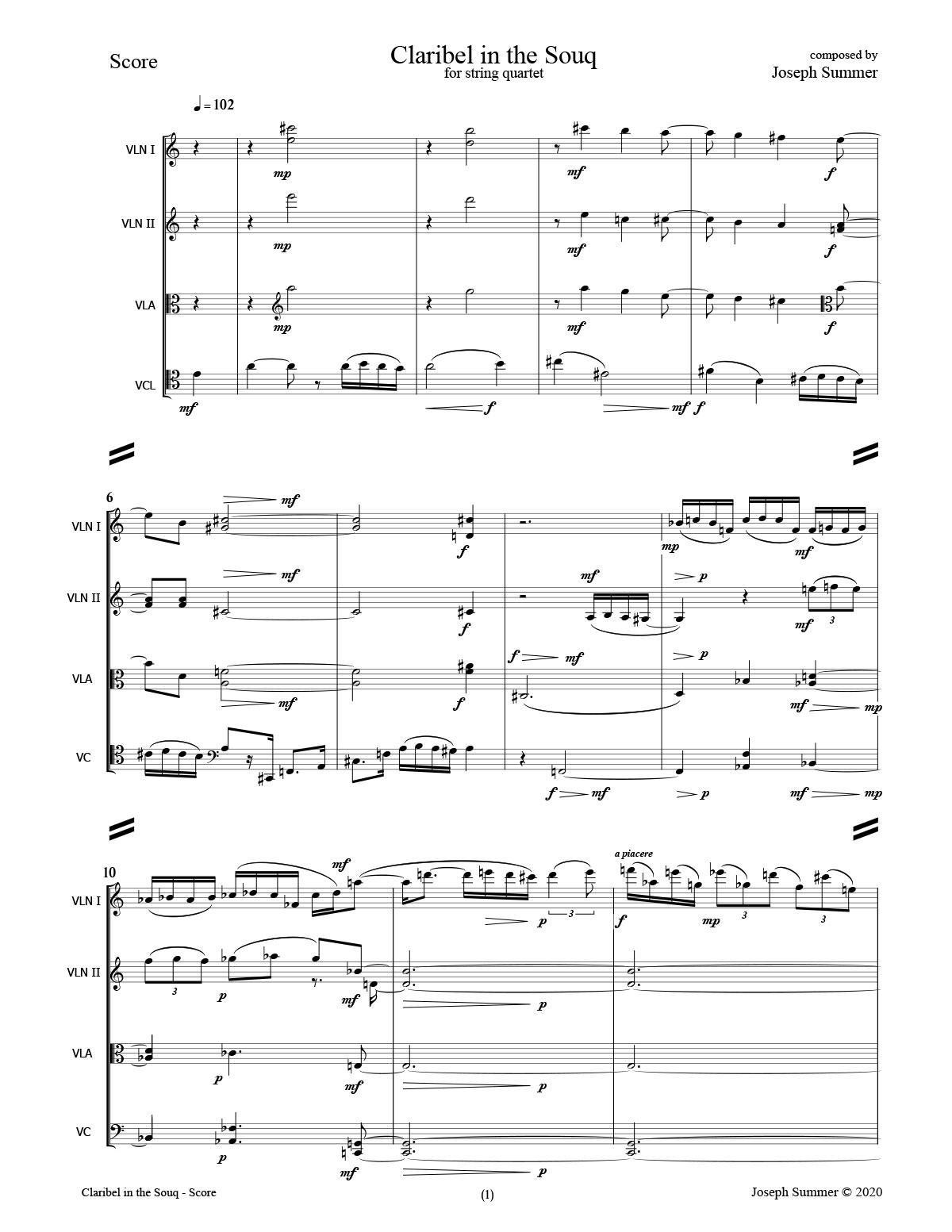

- Claribel in the Souq

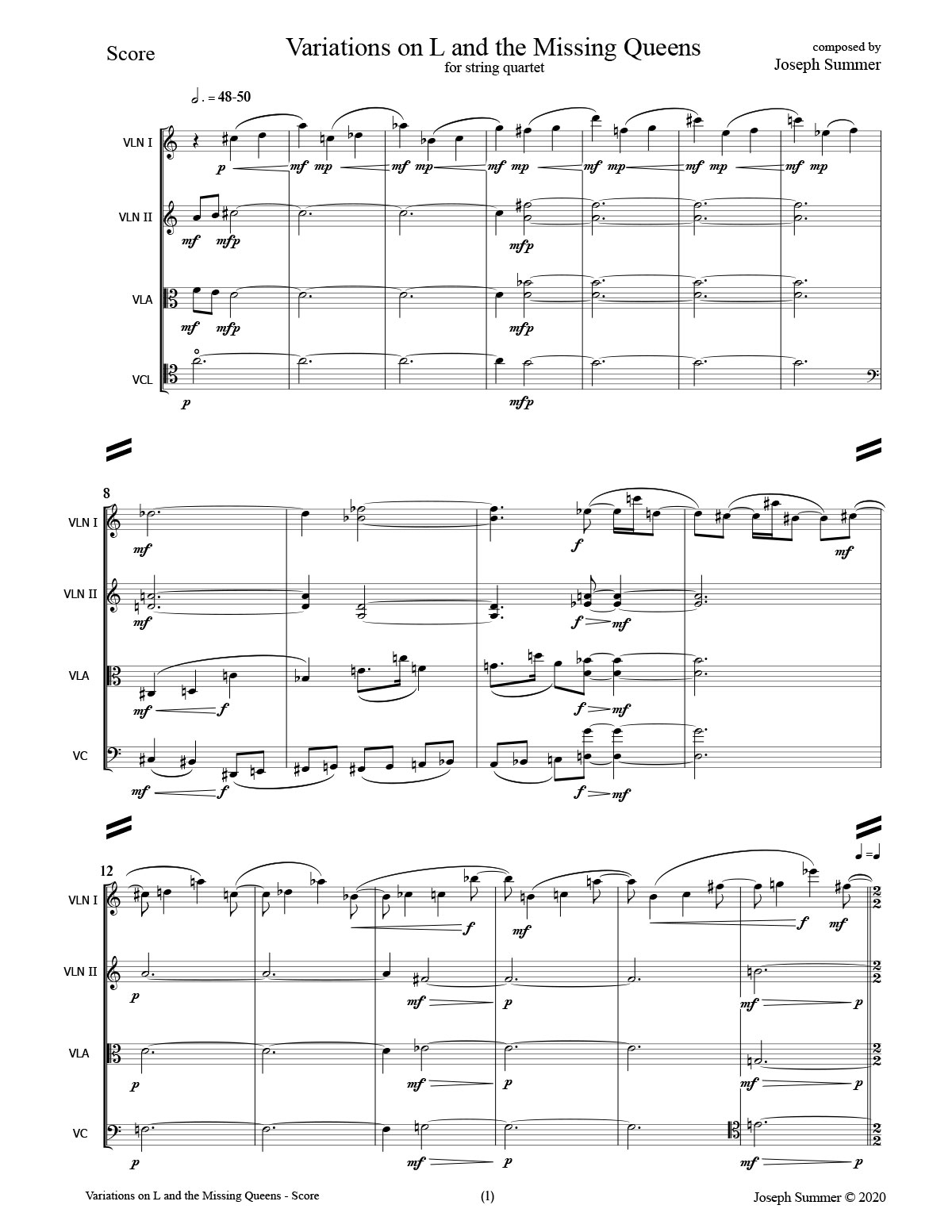

- Variations on L and the Missing Queens

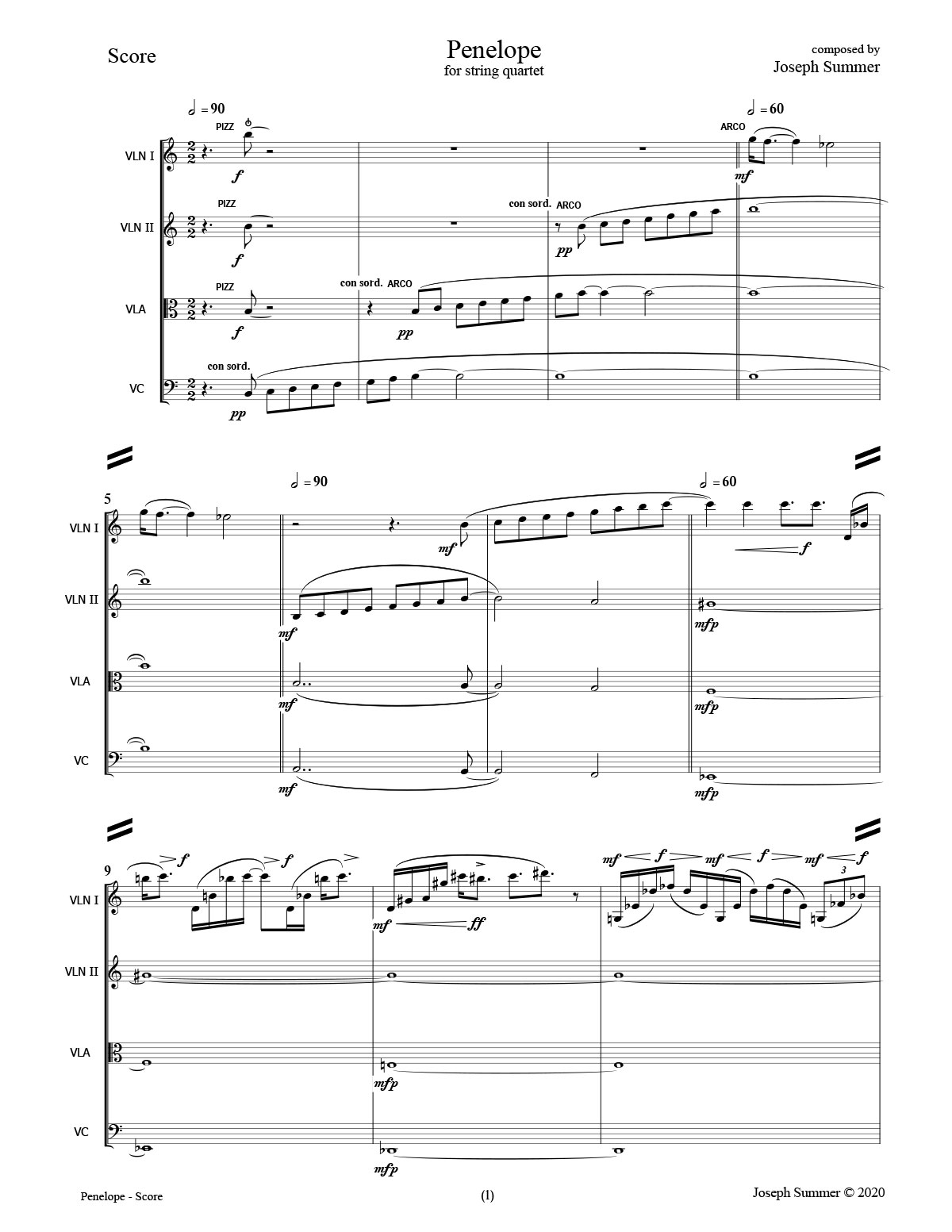

- Penelope

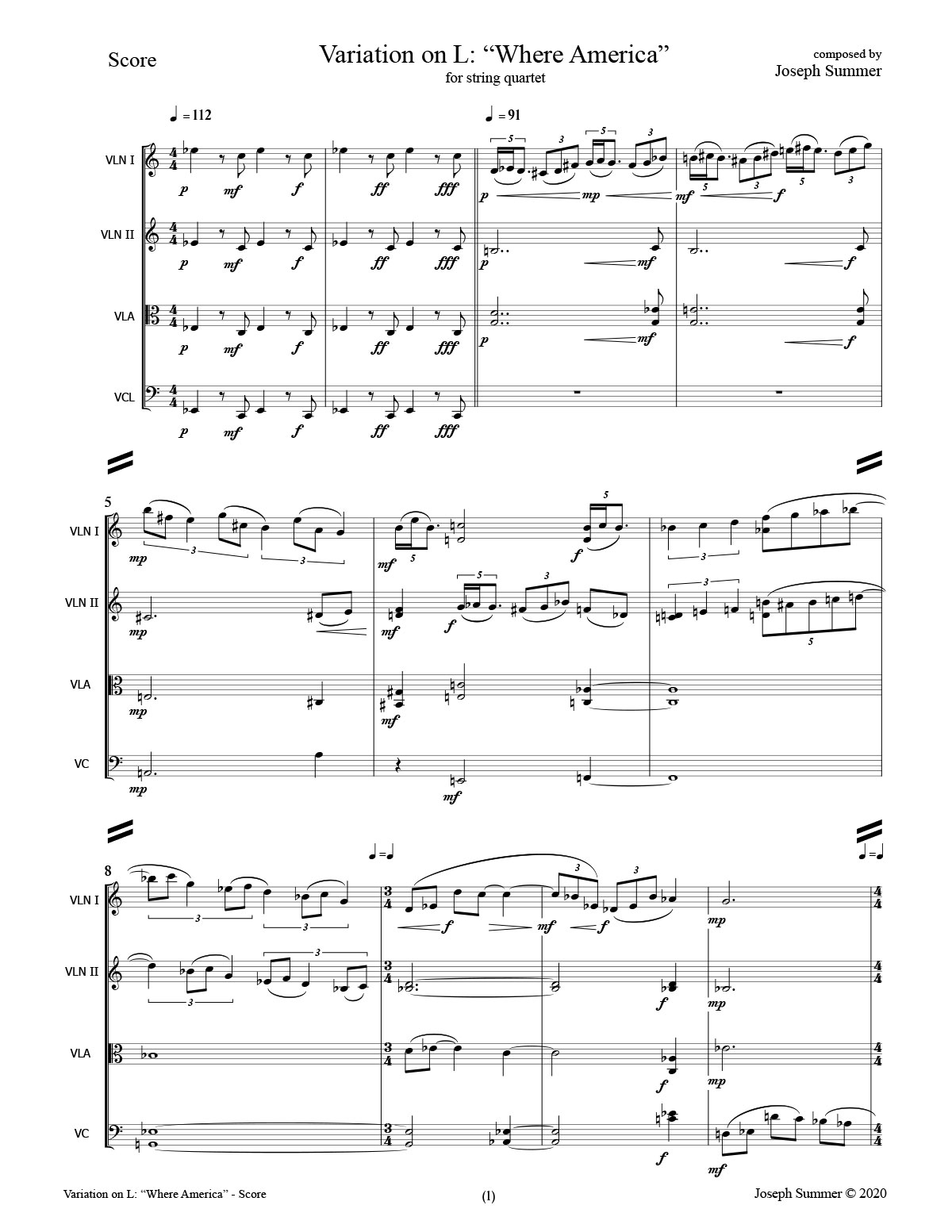

- Variations on L: “Where America”

- Selene Lourone, an invisible girl

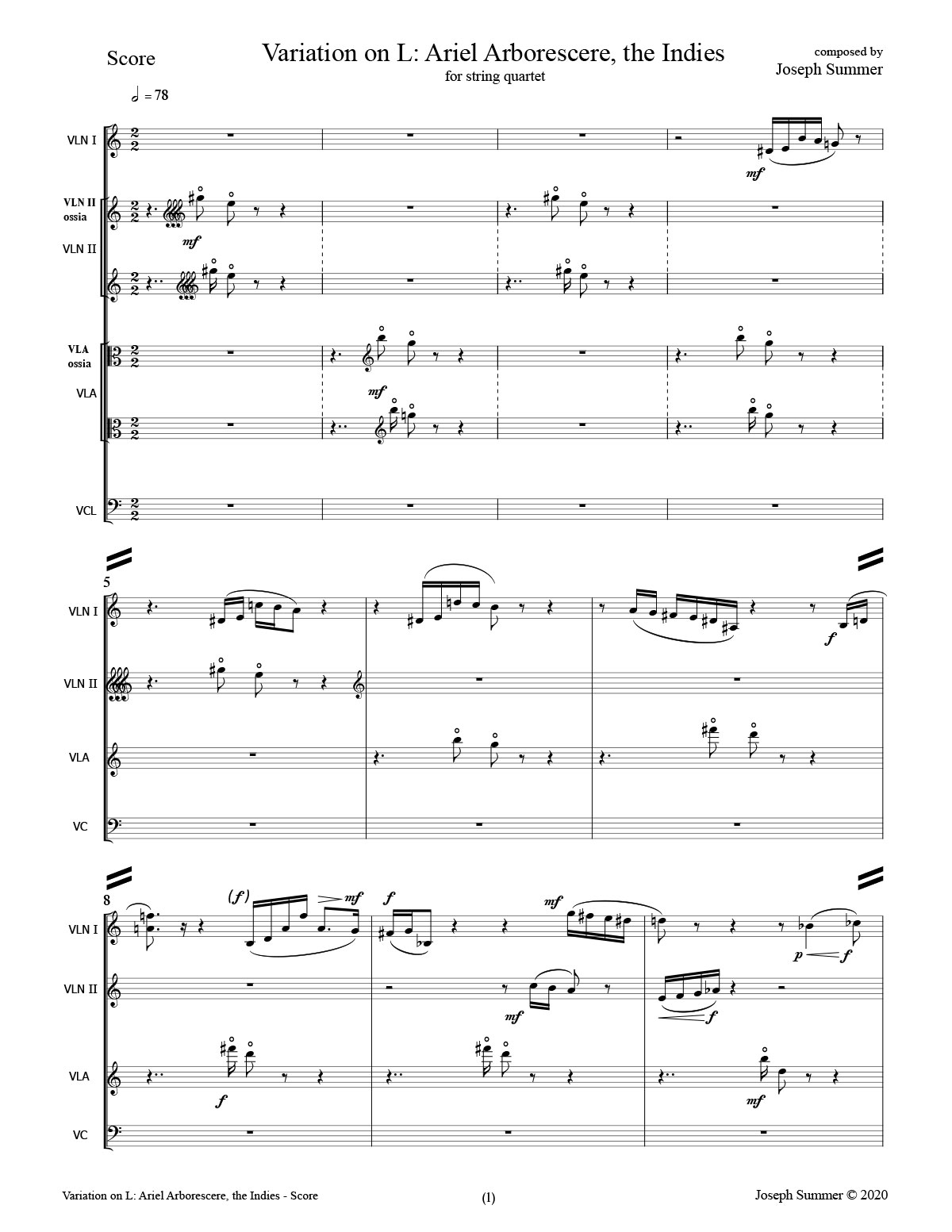

- Variations on L: Ariel Arborescere, the Indies

I wanted to write a string quartet that could unfold in many different ways, not in the standard linear collection of one to four (or slightly more) movements. I thought, “what if a quartet could be made in which the performers themselves shaped the work, found their own ‘container’ for the musical material?” I was also at the same time thinking about characters that are mentioned in plays (and other literary forms) but do not appear. Immediately I thought of Sycorax and Claribel, two characters in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, who are instrumental in the unfolding of the plot; and yet neither of which appear in person in the play. I had written short musical motifs for them, which appeared in my opera, The Tempest, and yet, after their minimal appearance, those brief musical moments vanish.

Beginning with the characters Sycorax and Claribel, I constructed two pieces about each of them individually; and consequently, the idea for “The Book of Invisible Women” became clear to me. I would write a musically coherent work of nine movements (later changed to ten), each of which movement would describe a character from literature who was “invisible,” who did not appear within the work in which the character ostensibly exists. Moving forward, I realized that I knew many invisible women characters, but not so many men. It seemed that many authors, including of course Shakespeare, had consigned female characters to air, to merely the words spoken by other imaginary – yet present – characters. What was to be a collection of pieces about invisible characters became a work about invisible women.

I wrote a musical theme to represent all the invisible women in Shakespeare, but then expanded that to represent the invisible woman in literature. I used the theme to tie together all the invisible characters and all the movements This theme metamorphosizes throughout the ten movements, but it also occupies the musical foreground in half the movements. In addition, I also incorporated female characters that appear but are mute, are not permitted to speak, and as well, female characters who speak but are never seen! The many forms of invisibility preoccupied me for the year and a half I spent writing the work.

As I constructed the book, I decided that the shape of it should be malleable, subject to the contemplation and aesthetic desiderata of the performers. Therefor, I wrote the ten movements to be performed in any group, in any order, as chosen by the performing quartet. I have deliberately made the numerical order of the quartets (1, 2, 3 . . . 10) not the “correct” or “ideal” order, but simply an unordered list, a menu. The performing quartet can play any number of movements, and in any order; as they desire. I’m curious to see different versions. I deliberately wrote too many movements and too lengthy a total duration to allow for a quartet to choose to do all ten in order without at least a pause.

Each movement has its own character, and story. Some movements contain the stories of more than one invisible character.

Individual Movements from The Book of Invisible Women

Follow the links below to purchase individual movements from The Book of Invisible Women.

String Quartet

Duration: approximately 12'

String Quartet

Duration: approximately 14'

String Quartet

Duration: approximately 3'

String Quartet

Duration: approximately 12'

String Quartet

Duration: approximately 6 minutes